|

|

? ?  ? ? |

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

|

|

Year : 2014? |? Volume : 3? |? Issue : 2? |? Page : 79-84 |

|

A clinical and radiographic retrospective analysis of talon cusps in ethnic Indian children

NB Nagaveni1, KV Umashankara2

1?Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, Karnataka, India

2?Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Bapuji Dental College and Hospital, Davangere, Karnataka, India

| Date of Submission |

26-Feb-2014 |

| Date of Acceptance |

18-Apr-2014 |

| Date of Web Publication |

6-Aug-2014 |

Correspondence Address:

N B Nagaveni

Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere - 577 004, Karnataka

India

DOI: 10.4103/2278-9588.138214

Objective: To report a detailed clinical and radiographic retrospective analysis of 21 talon cusps in Indian children.

Materials and Methods: A retrospective analysis of 21 talon cusps was conducted in children examined in the period from 2003 to 2008. Patients found with talon cusps underwent complete clinical and radiographic examination and 21 talons were evaluated for gender distribution, affected dentition and teeth, symmetry, type of talon, radiographic findings of pulp extension and associated complications as well as the treatment required.

Results: The study found 13 male patients (68.42%) and six female patients (31.57%) with talon cusps. Talon cusps were diagnosed in both primary (1 talon - 4.76%) and permanent dentition (20 talons - 95.23%). Of the 21 talons, 18 (85.71%) were found in the maxillary arch and three (14.28%) in the mandibular arch. In the maxilla, two talons (11.11%) were found in the permanent right central incisor, another two (11.11%) in the permanent left central incisor, seven (38.88%) in the permanent right lateral incisor and five (33.33%) in the permanent left lateral incisor. One talon (5.55%) was diagnosed in the mesiodens. In the mandible, two talons (66.66%) were found in the permanent left central incisor and one talon (33.33%) in the permanent right central incisor. Ten talons were type 1 talons (47.6%), seven were type 2 (33.33%) and four (19.04%) were type 3 talons. Thirteen of the talons (61.90%) had pulp extension into the cusp. In five talons (23.80%), occlusal interference was observed which required gradual grinding, 12 (57.14%) had very deep developmental grooves and required sealant application. One talon (4.76%) required extraction, as it was associated with the mesiodens.

Conclusion: Talon cusps may present either as an isolated entity or associated with other anomalies. Studies involving a large number of subjects are required to find more unusual variants of the talon cusp.

Keywords:?Bifid talon, mesiodens, primary incisor, retrospective study, talon cusp

How to cite this article:

Nagaveni N B, Umashankara K V. A clinical and radiographic retrospective analysis of talon cusps in ethnic Indian children. J Cranio Max Dis 2014;3:79-84 |

How to cite this URL:

Nagaveni N B, Umashankara K V. A clinical and radiographic retrospective analysis of talon cusps in ethnic Indian children. J Cranio Max Dis [serial online] 2014 [cited?2015 Feb 3];3:79-84. Available from:?https://craniomaxillary.com/text.asp?2014/3/2/79/138214 |

|

??Introduction |

? |

|

The talon cusp, a rare dental morphological anomaly, has been defined as an accessory cusp-like structure projecting from the cingulum area or the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) of the maxillary or mandibular anterior teeth in both primary and permanent dentition. [1] This anomaly is more commonly seen in maxillary teeth compared to mandibular teeth. It may occur unilaterally or bilaterally and can be seen either in primary or permanent dentition. [2] The exact etiology of this condition is unknown. It is thought to occur during morpho-differentiation as a result of outward folding of inner enamel epithelial cells (precursors of ameloblasts) and a transient focal hyperplasia of the mesenchymal dental papilla (precursor of odontoblasts) or a combination of genetic and environmental factors (multifactorial). [2],[3] It is composed of enamel, dentin and varying amount of pulp tissue. [2] It is known to be associated with some systemic conditions such as Mohr syndrome, [4] Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, [5] Sturge-?Weber syndrome?More Details, [6] and the ?Ellis-van Creveld syndrome?More Details. [7] It varies in size, shape, structure, location and the site of origin. Most talon cusps have been reported as case reports or case series in literature. Studies that have addressed the prevalence of talon cusps in different populations with a detailed description of clinical and radiographic characteristics are scarce. The aim of this article is to report a retrospective, clinical and radiographic analysis of 21 talon cusps that were diagnosed in an ethnic Indian child population with special emphasis on the type of talon.

|

??Materials and methods |

? |

|

A retrospective analysis of 21 talon cusps was conducted in 19 patients who were examined in the period from 2003 to 2008 at the Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry. The childrens' age ranged from three to 14 years. As talon cusps vary in size and shape, the diagnostic classification given by Hattab et al., [2] was used in assessing and classifying the talon cusps [Table 1]. Any accessory cusp-like structure projecting from the lingual surface of either the maxillary or mandibular teeth crown and extending like a small tubercle or to half the distance from CEJ to incisal edge was considered a talon cusp. All 19 subjects had talon cusps that were diagnosed both clinically and radiographically. Demographic data from the patients' case histories was obtained and variables such as age and gender, affected dentition and arch, affected tooth/teeth, unilateral/bilateralism, type of talon, radiographic findings of pulp extension and associated complications and treatment provided were evaluated.

|

Table 1: Talon cusp classification

Click here to view

|

|

??Results |

? |

|

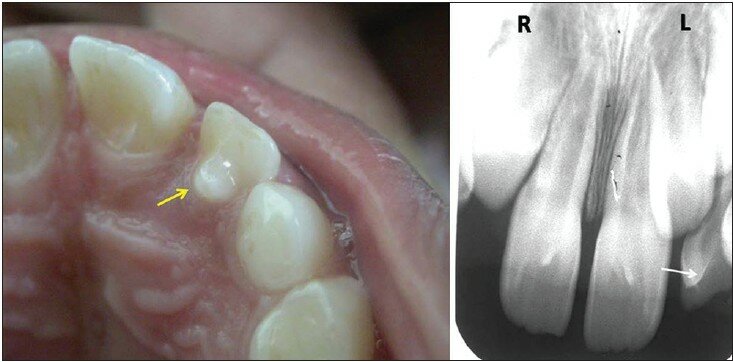

In a retrospective analysis of 21 talons observed in 19 children, 13 boys (65.42%) and 6 girls (31.57%) were found to have a talon cusp on their anterior teeth. The mean age of the children ranged from five to eight years. In this study, talon cusps were diagnosed in both primary (one talon - 4.76%) [Figure 1] and permanent dentitions (20 talons - 95.23%). Of the 21 talons, 18 (85.71%) were found in the maxillary arch, while only three talons (14.28%) were observed in the mandibular arch. In the maxilla, two talons (11.11%) were found in the permanent right central incisor, another two talons (11.11%) in the permanent left central incisor, seven talons (38.88%) in the permanent right lateral incisor and five (33.33%) in the permanent left lateral incisor. One talon (5.55%) was diagnosed in the mesiodens (supernumerary tooth). In the mandible, two talons (66.66%) were found in the permanent left central incisor [Figure 2] and one talon (33.33%) in the permanent right central incisor that was containing the dens invaginatus within the same tooth. Only one talon cusp (4.76%) was seen in the primary maxillary right lateral incisor. Most of the talons [17 (89.47%)] were unilateral; bilateral occurrence of talon cusps was seen in two patients only (10.52%) [Figure 3]. Ten talons were type 1 talons (47.6%), while seven were type 2 (33.33%) and four (19.04%) were type 3 talons. Thirteen of the talons (61.90%) had pulp extensions. Occlusal interference was observed in five talons (23.80%) which required gradual grinding followed by fluoride varnish application while 12 (57.14%) talons had very deep developmental grooves and required prophylactic sealant application to prevent the development of caries. One talon (4.76%) required extraction, as it was associated with the mesiodens [Table 2].

|

Figure 1: Clinical and radiographic image of talon cusp in primary lateral incisor (arrows)

Click here to view

|

|

Table 2: Clinical characteristics of talon cusps observed in 19 children

Click here to view

|

|

Figure 2: Talon cusp (arrow) in mandibular central incisor

Click here to view

|

|

Figure 3: Bilateral occurrence of talon cusps (arrows)

Click here to view

|

|

??Discussion |

? |

|

There is known variation in the prevalence rates of talon cusps in different ethnic populations. This may be due to the different criteria and definitions used to assess talon cusps or an actual variation of the condition among different nations, as well as variation in the samples examined. A 0.17%, 0.6% and 5.5% prevalence of the talon cusp has been reported by Buenviaje and Rapp, [8] Sedano et al.,[9] and Rusmah and Meon [10] in American, Mexican and Malaysian children respectively. Chawla and Tiwari [11] have reported a 7.7% prevalence in north Indian children. Gunduz and Celenk [12] showed 33 talons in 27 Turkish population. Recently, Hamasha et al.,[13] found a 0.55% prevalence in Jordanian adults based on radiographic examination only. The present study reports the clinical and radiographic analysis of 21 talons diagnosed in Indian children.

Our study found a majority of the talon cusps occurring in males as compared to females. This is in consistent with previous reports. [10],[11],[12],[13] However, there are other studies which show no gender prevalence. [8],[9] The occurrence of anomalous cusps is rather infrequent in primary dentition. The maxillary central incisor is the most affected tooth in the primary dentition. In this retrospective analysis, only one talon was found in the primary maxillary lateral incisor.

A review of literature suggests that the talon cusp has a striking predilection for the maxilla over the mandible with a majority of the cases occurring in maxillary anterior teeth. [2] A similar observation was made in this study. Reports of mandibular talon cusp are also rare in literature. Gunduz and Celenk [12] found only a three percent prevalence in mandibular central incisors, and another three percent in canines of a total 33 talons examined. In this study, three cases of mandibular talon cusps were found, one with a double talon on the right central incisor and one semi talon on the left central incisor, while the other was a co-occurrence of dens invaginatus and a talon cusp in the left central incisor.

All reported talon cusps in permanent teeth affected the maxillary lateral incisor most frequently followed by the central incisors and canines. [1],[2],[3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12] In the present study, the majority of the talons were found in maxillary lateral incisors which is in agreement with previous findings. However, Hamasha et al.,[13] found maximum prevalence in maxillary canines which may be due to a difference in the sample examined. The occurrence of the talon cusp in a facial talons is rare. It is even rarer in the mesiodens. mesiodens (supernumerary tooth) is an extremely rare phenomenon; only a few cases reported till now found a palatal talon. [2],[14],[15] Development of A rare combination of a facial talon cusp on a maxillary mesiodens was diagnosed in this study. Of a total of 21 talons, 10 were diagnosed as type I, seven as type II and four were of type III talons, a finding which is similar to the other study. [12]

Radiographically, the talon cusp appears similar to that of normal tooth structure presenting with radiopaque enamel and dentin, with or without extension of pulpal tissues. Typically, it looks like a V-shaped structure superimposed over the normal image of the crown. [2] Though several reports indicated talon cusps usually contain an extension of the pulp tissue, the identification of the pulpal configuration inside the talon cusp on a periapical radiograph is difficult due to superimposition. [2],[16],[17] Mader and Kellogg [18] suggested that large talon cusps especially when separated from the lingual surface of the tooth seem more likely to contain pulpal tissue. In our study, 13 of the talons had pulp extension into the cusp on radiographic examination. This finding was similar to finding reported by Gunduz and Celenk [12] in the Turkish group.

The complications of talon cusps may be functional, aesthetic, and pathological. A large talon is unaesthetic and presents clinical problems. [1],[3],[19] Functional complications include occlusal interference, trauma to the lip and tongue, speech problems and displacement of teeth. The deep grooves which join the cusp to the tooth may also act as stagnation areas for plaque and debris, become carious and cause subsequent periapical pathology. [19] The presence of a talon cusp is not always an indication for dental treatment unless it is associated with problems such as compromised aesthetics, occlusal interference, tooth displacement, caries, periodontal problems or irritation of the soft tissues during speech or mastication. [2],[3] The management and treatment outcome of talon cusp depends on the size, presenting complications and patient cooperation. Small talon cusps are asymptomatic and need no treatment. When there are deep developmental groves, simple prophylactic measures such as fissure sealing and composite resin restoration can be carried out. In case of occlusal interference, gradual and periodic reduction of bulk of the cusp along with application of topical fluoride to reduce sensitivity and stimulate reparative dentin formation for pulp protection or a total reduction of the cusp and calcium hydroxide pulpotomy can be carried out. It may also become necessary sometimes to reduce the cusps fully and carry out root canal therapy. In this retrospective analysis, the most common complication was the presence of deep grooves followed by occlusal interference. Therefore, prophylactic sealant was applied in 12 cases. In five talons, incremental grinding followed by fluoride varnish application had to be done because they caused occlusal interference. Extraction was carried out in one case as it was associated with the mesiodens.

It is essential to have precise criteria for categorization of an accessory cusp such as the talon cusp. Without standardization of terminology and firm diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of the talon cusp and its clinical significance cannot be reliably estimated and evaluated. To overcome these inconveniences, Hattab et al.,[2] had suggested a classification which has been used in this study. [2] This retrospective analysis of 21 talon cusps yielded two different clinical variants of talons which do not fit into the definition and classification of talon cusps given by Hattab et al.[2] [Table 1]. One is the occurrence of a facial talon on the mesiodens, and the other is a co-occurrence of the talon cusp and dens invaginatus in the same tooth. It is therefore recommended that the definition of the talon cusp be reconsidered and it should be extended to include supernumerary teeth as well as the facial surface. Mcnamara et al.,[20] and Jowharji et al.,[21] too have reported this anomaly and suggested that an alteration to the conventional definition of talon cusps be made, taking into consideration the talon cusps found on the facial aspect of teeth and the supernumerary teeth. There is insufficient data on the prevalence of talon cusps associated with other dental abnormalities. The present study found a variant of talon cusps i.e. a talon containing another anomaly like dens invaginatus and therefore studies involving large numbers are required to find more unusual variants of the talon cusp.

|

??Conclusion |

? |

|

Talon cusps are a rare odontogenic developmental anomaly of great clinical significance. They can occur as an isolated entity or with other odontogenic anomalies such as the mesiodens and dens invaginatus. The treatment plan varies with each individual case and the presenting symptoms associated with the particular talon cusp. Early detection is important to prevent complications.

?

|

??References |

? |

|

| 1. |

Davies PJ, Brook AH. The presentation of talon cusp: Diagnosis, clinical features, associations and possible aetiology. Br Dent J 1986;160:84-8.??

???? |

| 2. |

Hattab FN, Yassin OM, al-Nimri KS. Talon cusp in permanent dentition associated with other dental anomalies: Review of literature and reports of seven cases. ASDC J Dent Child 1996;63:368-76.??

???? |

| 3. |

al-Omari MA, Hattab FN, Darwazeh AM, Dummer PM. Clinical problems associated with unusual cases of talon cusp. Int Endod J 1999;32:183-90.??

???? |

| 4. |

Goldstein E, Medina JJ. Mohr syndrome or oral-facial-digital II: Report of 2 cases. J Am Dent Assoc 1974;89:377-82.??

???? |

| 5. |

Gardner DG, Girgis SS. Talon cusp: A dental anomaly in the Rubenstein-Taybi syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1979;47:519-21.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 6. |

Chen RJ, Chen HS. Talon cusp in primary dentition. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1986;62:67-72.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 7. |

Hattab FN, Yassin OM, Sasa IS. Oral manifestations of Ellis-van Creveld syndrome: Report of two siblings with unusual dental anomalies. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1998;22:159-65.??

???? |

| 8. |

Buenviaje TM, Rapp R. Dental anomalies in children: A clinical and radiographic survey. ASDC J Dent Child 1984;51:42-6.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 9. |

Sedano HO, Carreon Freyre I, Garza de la Garza ML, Gomar Franco CM, Grimaldo Hernandez C, Hernandez Montoya ME, et al. Clinical orodental abnormalities in Mexican children. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1989;68:300-11.??

???? |

| 10. |

Rusmah, Meon. Talon cusp in Malaysia. Aust Dent J 1991;36:11-4.??

???? |

| 11. |

Chawla HS, Tewari A, Gopalakrishnan NS. Talon cusp - A prevalence study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 1983;1:28-34.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 12. |

Gunduz K, Celenk P. Survey of talon cusps in the permanent dentition of a Turkish population. J Contemp Dent Pract 2008;9:84-91.??

???? |

| 13. |

Hamasha AA, Safadi RA. Prevalence of talon cusps in Jordanian permanent teeth: A radiographic study. BMC Oral Health 2010;10:6.??

???? |

| 14. |

Salama FS, Hanes CM, Hanes PJ, Ready MA. Talon cusp: A review and two case reports on supernumerary primary and permanent teeth. ASDC J Dent Child 1990;57:147-9.??

???? |

| 15. |

Nadkarni UM, Munshi A, Damle SG. Unusual presentation of talon cusp: Two case reports. Int J Paediatr Dent 2002;12:332-5.??

???? |

| 16. |

Gungor HC, Altay N, Kaymaz FF. Pulpal tissue in bilateral talon cusps of primary central incisors: Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;89:231-5.??

???? |

| 17. |

Lomcali G, Hazar S, Altinbulak H. Talon cusp: Report of five cases. Quintessence Int 1994;25:431-3.??

???? |

| 18. |

Mader CL, Kellogg SL. Primary talon cusp. ASDC J Dent Child 1985;52:223-6.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 19. |

Goel VP, Rohtagi VK, Kaushik KK. Talon cusp: A clinical study. J Indian Dent Assoc 1976;48:425-7.??

???? |

| 20. |

McNamara T, Haeussler AM, Keane J. Facial talon cusps. Int J Paediatr Dent 1997;7:259-62.??

???? |

| 21. |

Jowharji N, Noonan RG, Tylka JA. An unusual case of dental anomaly: A 'facial' talon cusp. ASDC J Dent Child 1992;59:156-8.??

???? |

? [Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Figure 3]

?

?

? [Table 1], [Table 2]

|

|

? ?  |

|

|