|

|

? ?  ? ? |

| ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

|

|

Year : 2012? |? Volume : 1? |? Issue : 2? |? Page : 79-86 |

|

Maximal mouth opening in Indian children using a new method

Arun Kumar1, Richa Mehta2, Mahesh Goel3, Samir Dutta1, Anita Hooda4

1?Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, Postraduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Haryana, India

2?Department of Prosthodontics, Government Dental College and Hospital, Patiala, Punjab, India

3?Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Postraduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Haryana, India

4?Department of Oral Anatomy, Postraduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Haryana, India

| Date of Submission |

15-Sep-2012 |

| Date of Acceptance |

30-Nov-2012 |

| Date of Web Publication |

8-Jan-2013 |

Correspondence Address:

Arun Kumar

Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, Postgraduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana

India

DOI: 10.4103/2278-9588.105680

Background: Measurement of normal maximum mouth opening (MMO) in children is an important diagnostic criterion in the evaluation of the stomatognathic system. The aim of this study was to determine the MMO in children from the Indian population, of age six to twelve years, and to examine the possible influence of age, gender, height, and body weight on MMO. Assessment of MMO was accomplished with a modified Vernier Caliper, by measuring the distance between the incisal edges of the upper and lower incisors during maximal mouth opening up to the painless limit.

Materials and Methods: The study consisted of 856 children from various schools in the city of Rohtak (Haryana), India, who were randomly divided into three groups based on their age: Group 1: Children of age six to eight years; Group II: Children of age eight to ten years; Group III: Children of age ten to twelve years. For each subject three readings were recorded in millimeters and the mean value was considered. The age, gender, height, and body weight of each child were also recorded at the same time. A P value of < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results: The results of the present study revealed that MMO in Indian children were 46.04 mm, 48.53 mm and 52.38 mm for boys and 45.95 mm, 47.27 mm and 52.05 mm for girls, in the age groups of six to eight, eight to ten, and ten to twelve years, respectively.

Conclusion: Significant associations were observed in between age, height, body weight, and MMO. However, no gender difference was observed.

Keywords:?Incisal edge, maximal mouth opening, Vernier Caliper

How to cite this article:

Kumar A, Mehta R, Goel M, Dutta S, Hooda A. Maximal mouth opening in Indian children using a new method. J Cranio Max Dis 2012;1:79-86 |

How to cite this URL:

Kumar A, Mehta R, Goel M, Dutta S, Hooda A. Maximal mouth opening in Indian children using a new method. J Cranio Max Dis [serial online] 2012 [cited?2013 Aug 27];1:79-86. Available from:?https://craniomaxillary.com/text.asp?2012/1/2/79/105680 |

|

??Introduction |

? |

|

Maximal opening of the mouth has been described either as the inter-incisal distance at maximal mouth opening or as the inter-incisal distance plus the overbite. [1] Mouth opening is commonly used as a practical standard diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular junction (TMJ) disorders. Limitation of mouth opening can be related to many clinical conditions such as temporomandibular disorders, [2] odontogenic infections, oral malignancies, submucous fibrosis, mandibular fractures, myopathies, and trauma. [3] All clinicians dealing with the oral cavity are faced with varying degrees of difficulty when mouth opening is limited.

As an important step, before diagnosis of decreased mouth opening, it is essential to establish what constitutes normal opening for the population. To date, the number of studies reporting the range of mouth opening is limited and the sample size in many is small. Therefore, the topic stresses a need for more studies, with a larger sample size, to draw a conclusion regarding MMO and its relationship with age, sex, height, and weight of a child.

Research has shown that measurement of MMO can vary with the age, [4],[5] gender, [4],[6] and height [7],[8] of a child. There is a broad agreement between authors that mouth opening reduces with age and that females have reduced mouth opening when compared with males. [4] Similar findings were also demonstrated by Yao et al. [6] and Hirsch et al. [9] regarding the influence of MMO values in different populations. Although the correlation with age is generally accepted, Landtwing [10] has stated that mouth opening correlates significantly less with age than with stature. A variation in the range of mouth opening is noted between different populations, [11],[12],[13],[14],[15] with populations of lower average stature having a lower range of mouth opening. However, Gallagher [7] found no link between mouth opening and stature in the Irish adult population.

As pointed out earlier, MMO is a valuable measure in the examination of children with functional disorders of the masticatory system and in the physiological stomatognathic system. The normal range of MMO in Indian children is missing or less well-established.

Therefore, the purpose of the present investigation is to obtain the normal range of mouth opening in children without functional disturbances of the masticatory system, and to examine the possible relationship between mouth opening, age, gender, height, and body weight.

|

??Materials and Methods |

? |

|

The study consisted of 856 subjects from various schools (17 schools) in the city of Rohtak (Haryana) India. Four hundred and fifty-seven boys and 399 girls between the ages of six and twelve years (mean age 10.02 + 0.05) were included in the study.

The patient history was taken and a questionnaire filled for each patient. This was administered at the time of clinical oral examination. The pre-tested, structured questionnaire consisted of demographic information on each child. The information collected included the age, gender, past history of any trauma, pain or clicking sound at rest or during jaw movements, and head and neck disorders. The child was also being asked to provide information on other types of conditions, such as, any systemic diseases, neurological disorders, or craniofacial deformities that would affect the ability to open its mouth.

The clinical examination consisted of a general dental examination of inspecting the preuricular area for any swelling, erythema, or tenderness. Palpation directly over the joint when the patient opened and closed the mandible was done. The extent of the mandibular condylar movement and temporomandibular joint auscultation was also done at the same time. The masticatory and cervical muscles were also palpated. The degree of mandibular opening was measured using the distance between the incisal edges of upper and lower anterior teeth. Deviation of the mandible during the opening was also observed.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were children with no history of jaw, head, or face trauma, no history of pain in the jaw, face, or neck, either at rest or during function, no history of severe bruxism, no facial or dental abnormalities, no history of temporomandibular joints sounds, and no dental prosthesis on the anterior teeth.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were subjects with severe orthodontic problems (anterior crossbite), neurological disorders and craniofacial deformities, systemic diseases (juvenile rheumatoid arthritis), and neck pain, which have been reported to create limited mouth opening.

A total of 167 subjects were excluded from the study following the above-mentioned criteria, because children with these conditions have been reported to have limited mouth opening. However, the present study measures the normal range of maximal mouth opening in healthy Indian children. Data contributed by this study will help in defining MMO in healthy Indian children, a field where limited documented studies exist.

Procedure for measuring maximal mouth opening

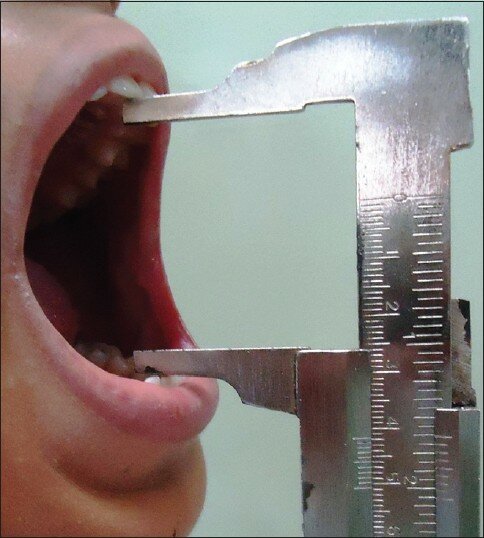

After obtaining informed consent from the respective school authorities, a clinical examination was performed. The MMO measurement was recorded by asking each of the subjects to open their mouths as wide as possible, while the examiner measured the maximum distance from the incisal edge of the maxillary central incisor to incisal edge of mandibular central incisor at the midline. For each subject three readings were recorded in millimeters (mm) and the mean value was considered. The MMO measurements were taken using a modified Vernier Caliper, while the subjects rested their heads against a firm wall surface in an upright position [Figure 1].

|

Figure 1: Method for measuring maximum mouth opening in children using a modified Vernier Caliper method

Click here to view

|

The body weight was recorded in kilograms using a weighing balance (equinox) [Figure 2]. The height was measured, without shoes, in centimeters, using a metric scale.

|

Figure 2: Method used for measuring the weight of a child

Click here to view

|

All measurements were performed by a single examiner to avoid intra-examiner variability. The measurements of MMO were compared in children of different age groups. Similarly a correlation between the MMO and body weight and height were also observed.

Study protocol

The children were randomly allocated into three groups based on the age:

Group 1: Children of age six to eight years

Group II: Children of age eight to ten years

Group III: Children of age ten to twelve years

The MMO, body weight, and height were recorded in all three groups. The measurements of MMO were correlated with the body weight and height of the children in different age groups.

Statistical methods

The results were analyzed by using the statistical package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 17, Inc.; Chicago). The mean and standard error of mean (SEM) were calculated for the MMO. The Student's 't' test and Pearson's correlation coefficient test were used. P values < 0.05 were considered as significant. The Shapio-Wilk test was done (using SPSS 17 Inc.; Chicago) to test the normality of the data and to determine whether to accept or reject the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis was accepted (Sig. value of the Shapio-Wilk test was > 0.05). This further suggested that the study data were from a normally distributed population. Furthermore, a 95% confidence interval was set for the present study.

Vernier Caliper and its modification

A Vernier caliper is a precise instrument for measuring the linear dimension (length) of any object to an accuracy of a tenth of a millimeter or better. It is comprised of two jaws, one for measuring the outer dimensions (larger jaw) and the other for measuring the inner dimension (smaller jaw), which are attached to a fixed scale and a sliding (Vernier) scale [Figure 3] and [Figure 4].

|

Figure 3: The original form of the Vernier Caliper consisted of two jaws, one larger and one smaller, with two scales, Vernier (sliding) scale and main scale

Click here to view

|

|

Figure 4: Vernier (Sliding) and main scale readings

Click here to view

|

For the present study, the Vernier Caliper has been modified:

- The jaw used for measuring the inner dimension has been removed by machine grinding [Figure 5].

- The jaw used for measuring the outer dimension has been modified in such a way that it can be used for measuring both the inner and outer dimensions. This is achieved by grinding the outer edges of the larger jaw to make them straight, engaging the inner edges of an object (e.g. inter-incisal distance) to measure its dimension. The distance between the two outer straight edges of the larger jaws is 9 mm when the zero readings of the Vernier scale and main scale coincide [Figure 5].

In course of modifying the Vernier Caliper, a new formula was derived for measuring the inner dimension, using the larger arm that was being modified for the purpose. The Final Readings were taken after adding 9 mm to the original reading [Figure 5].

|

Figure 5: Modified Vernier Caliper (Smaller jaw is removed; outer edges of larger jaw are straightened. The distance between the two outer straight edges of the larger jaw is 9 mm when the zero reading of the Vernier scale and main scale coincide. Final Readings taken after adding 9 mm to the original measurement)

Click here to view

|

Final Reading = Original Reading + 9 mm

This is a pioneer method used for measuring MMO in children. The method is safe and simple to execute, reproducible, reliable even in small children, does not affect the sensitivity of the caliper, and it is easy to calculate the final reading by adding a simple numerical value to the original measurement. Furthermore, the modified caliper is much lighter in weight, compact, easy to manipulate, and less fearful, particularly to children.

|

??Results |

? |

|

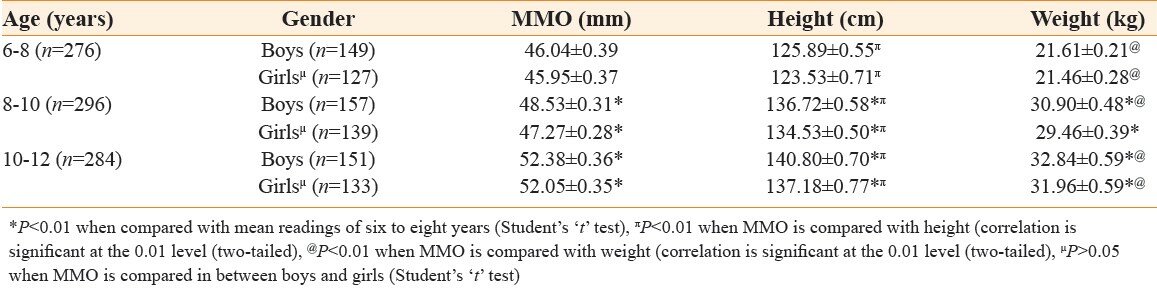

The MMO was measured in boys and girls aged between six and twelve years [Table 1]. The estimated average MMO measured for boys and girls at the age of six to eight years was 46.04 ? 0.39 mm and 45.95 ? 0.37 mm, respectively. The estimated average MMO measured for boys and girls at the age of eight to ten years was 48.53 ? 0.31 mm and 47.27 ? 0.28 mm, respectively. The estimated average MMO measured for boys and girls at the age of 10-12 years was 52.38 ? 0.36 mm and 52.05 ? 0.35 mm, respectively. There was a gradual increase in MMO with age, which was found to be statistically significant when compared between six and twelve year olds. However, no statistically significant difference was found in the MMO between boys and girls at various age groups [Table 1].

|

Table 1: Maximum mouth opening (mm), height (cm), and body weight (kg) in boys and girls of age six to twelve years (data presented as mean?SEM)

Click here to view

|

As shown in [Table 1] there was a gradual increase in the height of both boys and girls with age. The MMO was also found to increase with age. When compared statistically a significant difference was observed between the MMO and height of children at different age groups.

There was a gradual increase in the weight of both boys and girls with age. MMO was also found to increase with weight. A statistically significant difference was found between the MMO and weight at different ages. The results are shown in [Table 1].

|

??Discussion |

? |

|

The present study revealed that the MMOs in Indian children were 46.04 mm, 48.53 mm, and 52.38 mm for boys and 45.95 mm, 47.27 mm, and 52.05 mm for girls in the age groups of six to eight, eight to ten, and ten to twelve years, respectively. These values agreed well with the values, 46.0 and 46.2 mm, given by Nevakari [16] and Shephard and Shephard, [17] respectively, for children aged six to ten years, and the value of 46.4 mm given by Ingervall [8] for the opening capacity in seven-year-old children. Similarly, Ogura et al. [18] reported an average range of mouth opening of 49.5 mm in 10-year-old Japanese children. On the other hand, Muhtarogullary et al. [19] and Cortese et al. [20] reported lower values of MMO, that is, 38.2 mm and 38.59 mm, respectively, in children. The difference in MMO values reported by these workers could be due to different methodology used. In contrast, Vanderas [21] and Ingervall [8] reported higher values of MMO, that is, 54.8 mm and 51.3 mm, respectively, among children between the age of six and ten years. However, Landtwig [10] reported a mean value of 45.9 mm, regardless of the fact that the age range of the children was wider: five to nineteen years.

The MMO has been described either as the inter-incisal distance [14],[15],[17],[22] or as the inter-incisal distance plus the overbite. [11] Measurement of the inter-incisal distance plus overbite means measurement of the vertical distance traveled by the mandible. However, as pointed out by Mezitis et al. [14] the functional opening of the mouth is more important, because this is the value that actually affects the chewing and dental treatment. Hence, the inter-incisal distance has been used as a measurement of MMO in this study. Furthermore, the inter-incisal distance during active opening has been used as the MMO measurement in most studies [15],[17] An advantage of the incisal edge distance measurement is that the measuring point is relatively more permanent and more easily determined. An extraoral measurement was also used in some studies. [1] Wood and Branco [1] compared direct and extraoral measurements, and suggested that direct measurements using a ruler or Vernier caliper were more precise and accurate.

When measuring, the MMO head position is an important factor. [23],[24] Higbie et al. [25] described how the MMO decreases in the order of forward, natural, and retracted head positions. In the present study, the MMO was measured when the subject rested their heads against a firm wall surface in an upright position in order to eliminate the possible influence of different head positions.

With respect to horizontal mandibular movements in children, few data [26] were available in literature. In the present study, horizontal mandibular movements were not recorded, as it was difficult to get small children to perform these movements. Similarly, Bernal and Tsamtsouris [27] did not record protrusive and lateral movements in children with primary dentition. In contrast, Bonjardin et al. [26] trained 99 Brazilian children before measuring MMO, but it was not feasible to train every child before measuring MMO when the study consisted of a comparably larger sample size, as in the present case.

The MMO steadily increases after birth until adolescence [8],[17],[22],[28] and then gradually decreases as aging progresses. [11],[14] The present study reported a gradual increase in MMO in the different age groups of children. Findings were in agreement with Hirsch et al., [9] Cortese et al., [20] and Vandera, [21] where the MMO was found to be directly correlated with age. Abou-Atme et al. [29] reported a moderate-to-strong correlation between MMO and age in 102 Lebanese children, aged four to fifteen years. Rothenberg [30] noted a significant relationship between the maximum vertical opening of the mouth and age, in 189 Caucasian children, aged four to fourteen years. Sousa et al. [31] reported a weak significant correlation between the mandibular range of movement and age, in 303 Brazilian children, aged six to fourteen years. Certainly, it would be expected that with increase in age, the MMO also increased, particularly in children.

Few studies observed a gender difference in MMO in children. [9],[30] In the present study, a statistically significant difference was not observed in between boys and girls at various age groups. However, the MMO was found to be significantly different between the children of the six and eight year and ten and twelve year age groups, when compared. These findings in children were similar to the ones reported by many authors. [11],[20],[21] Similarly, Abou-Atme et al. [29] reported no gender difference in the measurement of MMO in 102 children aged four to fifteen years. In contrast, Pullinger et al. [32] observed that the maximum passive jaw opening measured inter-incisally by linear methods was 2.7% wider in young men than in young women. Similar findings were noted by Nevakari, [16] Gazit et al. [33] Solberg et al. [34] also. The possible reason for the negative correlation between MMO and gender in the present studies could be that the majority of male subjects studied were prepubertal or circumpubertal, hence, there were no extreme differences seen in facial size as might be expected in a more mature population. Furthermore, the fact that children did not diverge much for measurement of MMO suggested that such diversity develops later in life, probably due to late growth of young men.

The study revealed a definitive correlation between MMO and height and weight. Rothenberg [30] also observed a positive correlation between MMO values in relation to weight and height in subjects in the age group of four and fourteen years. Similar findings were observed by, Ingervall, [8] Landtwing, [10] Sousa et al., [31] and Henrikson et al. [35] On the other hand, Agerberg [11] found a weak correlation between MMO values in relation to height and weight in all age groups.

The observed gradual increase in MMO with increasing age, height, and body weight, as found in the present study, is due to changes in the temporomandibular joint apparatus, facial morphology, muscle development, and growth of cranial base and mandible, particularly in length. At present, it is difficult to propose the exact mechanism responsible for this increase in MMO. However, this study has used a modified Vernier caliper method, for the first time, to measure MMO in Indian children aged six to twelve years, and suggests a positive relationship between MMO, age, height, and body weight.

Assessment of the mouth opening is an important part of the clinical examination for a clinician or physician involved in the treatment of head and neck disorders. In order to diagnose an abnormality, knowledge of the normal condition is essential. The study, in combination with clinical expertise, serves as an available approach for clinical decision-making, to diagnose severe divergences and diseases related to the function of the masticatory system.

|

??Conclusion |

? |

|

- The MMO for Indian children is 46.04 mm, 48.53 mm, and 52.38 mm for boys and 45.95 mm, 47.27 mm, and 52.05 mm for girls at age groups of six to eight, eight to ten, and ten to twelve years, respectively.

- There is no gender difference in MMO between boys and girls.

- Age has a significant influence on the MMO values. MMO increases with age.

- A definite correlation exists between MMO and height. MMO is found to increase as height increases.

- Significant correlation is found between MMO and weight in boys and girls. MMO increases gradually with increase in weight.

- A simple and quick method for assessing and recording MMO has been presented.

?

|

??References |

? |

|

| 1. |

Wood GD, Branco JA. A comparison of three methods of measuring maximal opening of the mouth. J Oral Surg 1979;37:175-7.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 2. |

Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, LeResche L, Von Korff M, Howard J, Truelove E, et al. Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders: Clinical signs in cases and controls. J Am Dent Assoc 1990;120:273-81.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 3. |

Dworkin SF, LeResche L, DeRouen T, Von Korff M. Assessing clinical signs of temporomandibular disorders: Reliability of clinical examiners. J Prosthet Dent 1990;63:574-9.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 4. |

Szentpetery A. Clinical utility of mandibular movement ranges. J Orofac Pain 1993;7:163-8.??

???? |

| 5. |

Machado BC, Medeiros AP, Felicio CM. Mandibular movement range in children. ProFono 2009;21:189-94.??

???? |

| 6. |

Yao KT, Lin CC, Hung CH. Maximum mouth opening of ethnic Chinese in Taiwan. J Dent Sci 2009;4:40-4.??

???? |

| 7. |

Gallagher C, Gallagher V, Whelton H, Cronin M. The normal range of mouth opening in an Irish population. J Oral Rehabil 2004;31:110-6.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 8. |

Ingervall B. Range of movement of mandible in children. Scand J Dent Res 1970;78:311-22.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 9. |

Hirsch C, John MT, Lautenschlager C, List T. Mandibular jaw movement capacity in 10-17-yr-old children and adolescents: Normative values and the influence of gender, age, and temporomandibular disorders. Eur J Oral Sci 2006;114:465-70.??

???? |

| 10. |

Landtwig K. Evaluation of the normal range of vertical mandibular opening in children and adolescents with special reference to age and stature. J Maxillofac Surg 1978;6:157-62.??

???? |

| 11. |

Agerberg G. Maximal mandibular movements in young men and women. Sven TandlakTidskr 1974;67:81-100.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 12. |

Gaviao MB, Chelotti A, Silva FA. Functional analysis of deciduous occlusion: Evaluation of mandibular movements. Rev. Odontol. Univ. Sao Paulo 1997;11:61-9.??

???? |

| 13. |

Alamoudi N, Farsi N, Salako NO, Feteih R. Temporomandibular disorders among school children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1998;22:323-9.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 14. |

Mezitis M, Rallis G, Zachariades N. The normal range of mouth opening. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989;47:1028-9.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 15. |

Cox SC, Walker DM. Establishing a normal range for mouth opening: Its use in screening for oral submucous fibrosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;35:40-2.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 16. |

Nevakari K. "Elapsiopraearticularis" of the temporomandibular joint. A pantomographic study of the so-called physiological subluxation. Acta Odont Scand 1960;18:123-70.??

???? |

| 17. |

Sheppard IM, Sheppard SM. Maximal incisal opening: A diagnostic index? J Dent Med 1965;20:13-5.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 18. |

Ogura T, Morinushi T, Ohno H, Sumi K, Hatada K. An epidemiological study of TMJ dysfunction syndrome in adolescents. J Pedod 1985;10:22-35.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 19. |

Muhtarogullary M, Demirel F, Saygili G. Temporomandibular disorders in Turkish children with mixed and primary dentition: Prevalence of signs and symptoms. Turk J Pediatr 2004;46:159-63.??

???? |

| 20. |

Cortese SG, Oliver LM, Biondi AM. Determination of range of mandibular movements in children without temporomandibular disorders. Cranio 2007;25:200-5.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 21. |

Vanderas AP. Mandibular movements and their relationship to age and body height in children with or without clinical signs of craniomandibular dysfunction: Part IV. A comparative study. J Dent Child 1992;59:338-41.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 22. |

Weinstein IR. Normal range of mouth opening. Letters to the editor. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1984;42:347.??

???? |

| 23. |

Eriksson PO, Haggman-Henrikson B, Nordh E, Zafar H. Co-ordinated mandibular and head-neck movements during rhythmic jaw activities in man. J Dent Res 2000;79:1378-84.??

???? |

| 24. |

Visscher CM, Huddleston-Slater JJ, Lobbezoo F, Naeije M. Kinematics of the human mandible for different head postures. J Oral Rehabil 2000;27:299-305.??

???? |

| 25. |

Higbie EJ, Seidel-Cobb D, Taylor LF, Cummings GS. Effect of head position on vertical mandibular opening. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1999;29:127-30.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 26. |

Bonjardim LR, Gavi?o MB, Pereira LJ, Castelo PM. Mandibular movements in children with and without signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. J Appl Oral Sci 2004;12:39-44.??

???? |

| 27. |

Bernal M, Tsamtsouris A. Signs and symptoms of temporomandibular dysfunction in 3 to 5 year old children. J Pedod 1986;10:127-40.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 28. |

Miller VJ, Bookhan V, Brummer D, Singh JC. A mouth opening index for patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil 1999;26:534-7.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 29. |

Abou-Atme YS, Chedid N, Melis M, Zawawi KH. Clinical measurement of normal maximal mouth opening in children.Cranio 2008;26:191-6.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 30. |

Rothenberg LH. An analysis of maximum mandibular movements, craniofacial relationships and temporomandibular joint awareness in children. Angle Orthod 1991;61:103-12.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 31. |

Sousa LM, Nagamine LM, Chaves TC, Grossi DB, Regalo SC, Oliveira AS. Evaluation of mandibular range of motion in Brazilian children and its correlation to age, height, weight, and gender. Braz Oral Res 2008;22:61-6.??

???? |

| 32. |

Pullinger AG, Liu SP, Low G, Tayt D. Differences between sexes in maximum jaw opening when corrected to body size. J Oral Rehabil 1987;14:291-9.??

???? |

| 33. |

Gazit E, Lieberman M, Eini R, Hirsch N, Serfaty V, Fuchs C, et al. Prevalence of mandibular dysfunction in 10-18 year old Israeli school children. J Oral Rehabil 1984;11:307-17.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 34. |

Solberg WK, Woo MW, Houston JB. Prevalence of mandibular dysfunction in young adults. J Am Dent Assoc 1979;98:25-34.??

[PUBMED]???? |

| 35. |

Henrikson T, Nilner M, Kurol J. Signs of temporomandibular disorders in girls receiving orthodontic treatment. A prospective and longitudinal comparison with untreated Class II malocclusions and normal occlusion subjects. Eur J Orthod 2000;22:271-81.??

[PUBMED]???? |

? [Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Figure 3], [Figure 4], [Figure 5]

?

?

? [Table 1]

|

|

? ?  |

|

|